It is easy to get confused or distracted by all the jargon used in strategic planning: goals, tactics, strategies, directions, objectives, issues, activities, etc. No matter what terms you use, the information in a nonprofit strategic plan is often organized in layers. Understanding the purpose of these layers reduces the importance of their names, clarifies their role in planning, and suggests that different processes are needed for strategic planning and implementation planning.

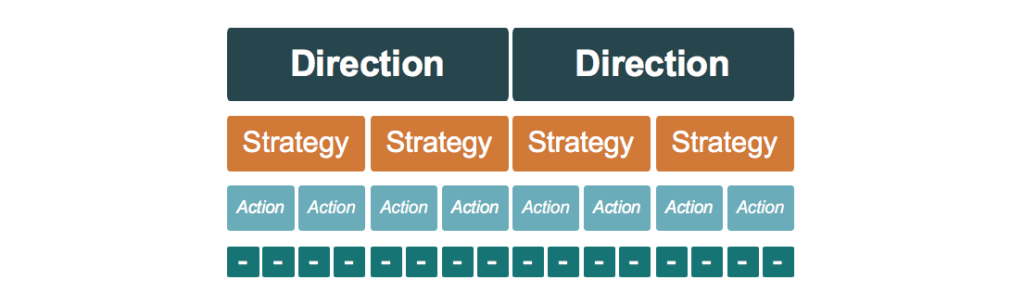

Here is a visual representation of the layers of a strategic plan. At the top are statements that are large in scope. We call them directions but they could be called goals, objectives or anything else. The name doesn’t matter. Below each statement are sub-items that give a little more detail to the large statements. We typically call the items in this layer strategies. There might be more sub-items for each strategy and so on. As you go down the statements get smaller in scope and might be called actions, tactics, tasks or anything else. All these layers give different levels of detail to the plan.

Strategy and Implementation

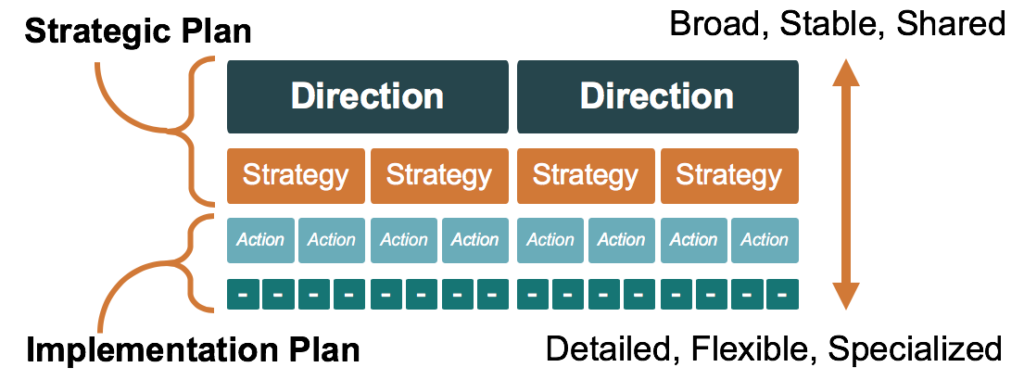

All of these layers might be in the strategic plan document, but we find it helpful to differentiate between the strategy portion of this diagram and the implementation portion.

The top half of the diagram is the strategic plan. The statements in the strategic plan are broad. They are big ideas, the big picture, 10,000 foot. People who like strategy and long-range planning think they are visionary and transformative, “Finally we are talking about what matters!” People who like implementation and action planning think they are vague and weightless, “Yeah, but what are we going to DO?”

Regardless of your opinion, because these statements are broad, they can be shared by everyone in the organization. Everyone can see a place for their work in these big statements. Everyone should be contributing in some way to their success.

And, these statements are intended to be stable. They are big enough that we aren’t expecting them to change much in 3-5 years. It is going to take that long to make progress on them.

The bottom half of the diagram is the implementation plan. The statements in the implementation plan are more specific, closer to the ground. They detail what we are going to do to achieve the strategic plan. People who like implementation think these statements provide useful, immediate direction, “Finally we know what we are actually going to do!” People who like strategy tire of all the details at this level, “We are in the weeds.”

Because these statements are specific, they are more specialized. Not everyone is going to have a place in each action in the implementation plan. People and departments are going to split them up and take responsibility for them accordingly.

And, these statements are much more flexible. The closer you get to the ground, the more willing you have to be to adapt your plan to changes in the landscape. Unlike the goals and strategies, we expect these more specific actions and tasks to change over the period of the strategic plan. At the beginning, we certainly don’t know all of the specifics of what needs to be done to move the strategic plan forward. We must have a process to incorporate these additions and changes, otherwise the plan will become irrelevant and unused.

Reasons for Separating Strategy from Implementation

Sometimes a strategic plan document includes both strategy and implementation. We find it helpful to split them into two documents. Why?

First, staff and board tend to go into strategic planning with the idea that they are creating a 3-year plan or a 5-year plan (for example). It will not need substantial updates until the end of that period. This is fine for the strategy part of the plan because it is intended to be broad, stable, and shared. But, because implementation planning must be detailed, flexible, and specialized, it’s not possible to create a useful 3-year or 5-year implementation plan. Implementation plans should be created for a shorter period (e.g. one year) and regularly revised. If the implementation plan is seen as a part of the 3- or 5-year plan, people are less likely to do the work to update it in the interim and it will become outdated.

In the same vein, a strategic plan is approved by the board, a process that is not very fast or flexible. Again, this is fine for the broad and stable top layers. But, changes to the implementation plan should not need approval by the board. Board approval adds a barrier to the work of the staff and bogs the board down in details they don’t need.

Take a look at your last strategic plan. Does your plan have layers? How well did your organization understand the purposes of those layers? How did staff and board differentiate between strategy and implementation?